Impressions

Impressions of Visitors and Important People

Tony Gaston (Ottawa, Canada)

I first visited the upper Beas Valley in 1969, when Manali had only two guest houses and a government run tourist bungalow; when Manikaran could scarcely be reached by jeep, and before the road up the valley and across Rhotang Pass was funneling a thousand trucks a week into Lahaul and Spiti. I loved the valley then, but already it was clear that natural ecosystems were in retreat. In fact, after several visits to Himachal in the early 1970s, I began to believe that there was no such thing as an undisturbed temperate forest in the state.

Then, in 1973, inspired by Penelope Chetwode’s book (“End of the Habitable World”) on Kullu, my wife, Anne-Marie and I trekked across the Bashleo Pass from Rampur to Inner Seraj and saw for the first time the wonderful forests of the Upper Tirthan. It was that trek, through luxuriant oak and rhododendron forests, beside crystal, sparkling streams, seeing signs of bears, martins and leopards, and hearing the hoarse calls of the Koklas pheasants at dawn, that convinced me that the true ecology of the Western Himalayas still existed in these remote valleys. From those early glimpses grew the Himachal Wildlife Project, the dream and hard work of many, both in India and abroad. Through this vision, the tenacity of Forest Officers, and local enthusiasts, the great wilderness area known now as the Great Himalayan National Park was created.

No one could reach the high meadows of Tirath or Dhel and be unmoved by the clearness of the air, the great vista of the peaks, and that sense of freedom that comes with leaving behind all artificial light, all mechanical transport, all trace of industrial civilization. The headwaters and high peaks of Inner Seraj have been places of pilgrimage for local people since time immemorial. Once again they can be places of veneration for a new generation of pilgrims. Those for whom wilderness and the creatures that depend upon it are symbols of a better world: a world of harmony, where nature lives out its age-old drama of life and death, unaffected by the dissonance of the modern world.

But beware! If you venture into the Himalayan wilderness, you run the risk of becoming a stranger in the common world. We who have been brushed by these places are forever changed; the goals of ambition and desire become muted when touched by the immensity and grandeur of the great mountains. To wander alone in these high places, however briefly, is to become a prey to yearnings that can never be extinguished or denied. Even in the cities of the West, my mind returns ever and again to that beauty, that awe, that freedom, that I knew where the Sainj and Tirthan are born, among the snowy peaks. To deny such experiences to future generations by failing to protect such places now would be an act of enormous folly. The Great Himalayan National Park is a jewel in the crown of Himalaya.

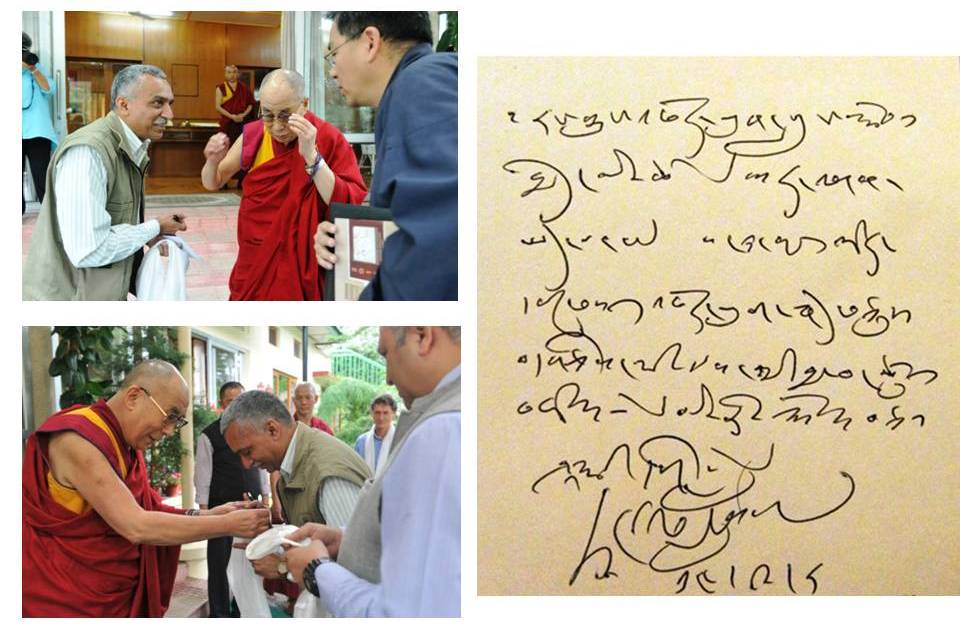

His Holiness, Dalai Lama

With my prayers for your success.

Buddhist Monk

Dalai Lama

September 8, 2014″ – in Dharamshala.

Poet, writer Gulzar

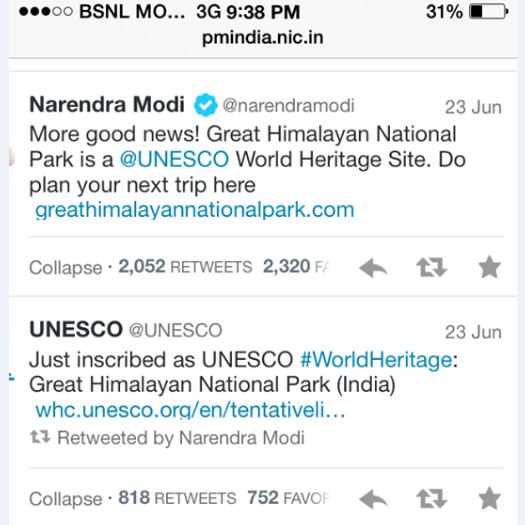

Hon’ble Prime Minister of India Shri Narendra D Modi

Impressions of Dr. Jeff Salz

“The reason of adventure is where it takes you – internally, but also… just today, coming around the turn on the trail, I looked down and I saw this incredible view of flowers blooming in the green grass, clouds loosing themselves in the trees, and the trees coming in the views and disappearing, it was just breathtaking for me, and I have this moment of feeling that this is what makes life worth living. In all the daily hubub it is easy to forget the incredible beauty and magnificence of life, just the sheer glory of life. And you do not see it in day-to-day experience – so adventure is thing that lives us beyond the ordinary and puts us in touch beyond the extraordinary” explains Jeff Salz while describing his experiences of a trek to the Tirthan Valley of the Great Himalayan National Park. Jeff, from USA represents, the new breed of “ecotourists.” Increasingly people, especially the young, are now attracted to remote forest areas, adventure and serious trekking. Students from city schools all over the country arrive annually in large numbers and enjoy a variety of nature-based activities.

Payson R. Stevens, a Prominent Friend of GHNP

“I want to let you know, with profound and quiet appreciation, that the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP) was inscribed yesterday as a UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS) in Doha. This is another wonderful phase of my 14-year association with GHNP as a trekker (1,500 km), advisor, and lover of this truly unique environment in India and our planet.

A very small informal group, Friends of GHNP, played a crucial role in making this happen, along with a handful of dedicated Indian scientists and government officials who understand the importance of GHNP: a place protecting the Western Himalayas by Indian environmental law and now internationally recognized as a World Heritage Site committed to conserve the unique biodiversity of the Western Himalayas.”

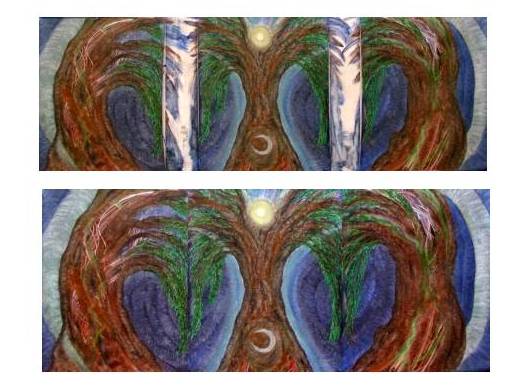

(Payson R. Stevens divides his time painting/writing/film-making in the studios in Del Mar, California http://www.energylandscapes.com and a remote part of the Indian Himalayas (Kullu Valley) where he lives with his wife, the writer Kamla K. Kapoor www.kamlakkapur.com).

G.S. Rawat (Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun)

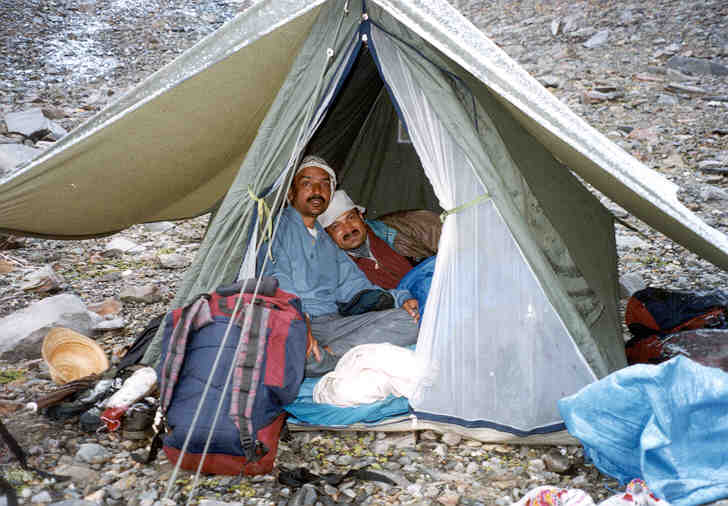

November 1999, Pin-Parvati Pass Trek

September 9,1999 happens to be one of the memorable days of my recent journey in the Himalayan mountains. I was one among the 29 members who crossed the treacherous Pin-Parvati Pass (5319 m) in Kullu district of Himachal Pradesh (HP). My memory is vivid with the early afternoon of that day when I was alone for some time. As I stood on a large ice field near the pass, awestruck by the majesty of Great Himalayan snow peaks all around, I thanked my stars for being there. The weather had just cleared after a brief snowstorm and our prospects of crossing the pass seemed brighter. However, the mountain slopes below the ice field were still under cloud cover.

Blowing my numb fingers and wiping my running nose, I looked for Punjab Singh, our guide and relentless hero of the trek. He was nearly 20 m ahead of me, poking a bamboo stick into the ice (to look for the crevices) and gradually moving ahead. Nearly 45 years old, little over 6 feet tall with solid built, and popularly known as “Ibex” among his friends, Punjab Singh serves as a Beat Officer in Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary. Our team leader Mr. Sanjeeva Pandey, Director, Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP), Mr. A.C. Sharma (DFO Parvati Valley), their staff members and porters were waiting for our signals some 300 m below the ice field. Mr. V. Jishtu from State Forest Research Institute, Shimla and Mr. Inder Paul, a 52 year old photographer from Shimla, were the other team members.

At around 13:30 hrs, Punjab Singh had left us behind discarding an easier looking approach towards the pass, and taken a more difficult detour. This, coupled with rough weather and ill health of a few members, had caused some of us to be very concerned. Other teammates had even raised serious doubts about Punjab Singh’s knowledge of the area and proposed to return back to the base camp that was some 4 kms down the valley. I had been asked to closely follow Punjab Singh and find out from him whether he was very sure about the route, and also assess if all the party members would be able to negotiate the trail left by him. I had a walkie-talkie to maintain a constant communication with our party.

I called Punjab Singh back to the place where I was standing and expressed our concern. He came smiling, showed me location of the pass and explained that no one could be absolutely sure about the approach in such areas due to ever changing snow and ice conditions. He also told us that the easy looking approach, which he had decided against, ended at a steep ice wall that could not be climbed without proper mountaineering gear. Only then did I realize why one trekking party had returned back to Manikaran two days before, following an unsuccessful attempt at crossing the pass. From Punjab Singh’s facial expressions I could clearly read his silent message: “You guys better believe and follow me without wasting time.”

It was already 14 30 hrs. We feared if the party didn’t cross the pass before 17 00 hrs or so, it could result in a disaster as we didn’t have enough equipment to camp on the snow and the weather could change at anytime. Some of the trekkers were suffering due to insufficient clothing and bad shoes. Immediately I contacted Mr. Pandey stating that Punjab Singh had taken the best possible route and the team should advance without any further delay. After half an hour or so the team members started arriving on the ice field one by one, cheered by Mr. Pandey and Mr. Sharma. Punjab Singh continued his ice poking forays and led the group steadily towards the pass. By 16:30 hrs all of us were on the pass greeting and hugging each other!

I could see the tears of joy streaking on the cheek of our team leader. Having offered our prayers for a wonderful and lucky day we quickly descended on the other side of the pass to a place called Thangpat (5000 m) before it was dark. That was the fourth and most crucial day of our Pin Parvati Pass trek, which started on 6th September, 1999 from Barshaini village (2150 m) in Parvati Valley. Although several trekking parties and local shepherds have traversed through the Pin Parvati Pass, it still remains a remote trek largely due to its rugged and distant terrain. The inner area of Parvati valley has recently been included in GHNP and it adjoins Pin Valley National Park. These protected areas, flanked by Rupi-Bhaba Sanctuary on the east, form one of the richest biodiversity and contiguous conservation areas in Himachal Pradesh.

Arnold Lippin (Brooklyn, New York)

Sainj-Tirthan Trek, October 2000

At 57 years I had just been down-sized after working 30 years. Payson, my closest friend of 38 years, calls with an invitation to go trekking in a new national park in the Indian Himalayas. Although I have savings to tide me over, I feel I should be looking for another job and decline. As soon as I hang up I realize this was the wrong decision and call back to accept. I am warned to get in good physical shape and start riding my bicycle everywhere to build up my wind and strength.

We arrived at Neully the starting point of our seven day trek through the Sanji and Thirtan river valleys. The first day is 21 km of easy walking along wide trails adjacent to the Sanji river. We pass numerous villages with corn drying on the roofs and people preparing their fields with oxen and wooden ploughs. In one of the villages we eat delicious roasted corn and our offered payment is only accepted with much insistence.

At dusk, I round a bend in the trail to see a flash of red crossing before me. Payson catches the last of its form as the large bird disappears into the forest. We have been blessed with a sighting the rare (and never photographed in the wild), Western Tragopan. This great pheasant is the symbol of the Great Himalayan National Park we are about to enter and we take it to be a very good omen.

The river is a constant rushing companion, strewn with giant boulders deposited by eons of moving water. We stop at the highest waterfall in the Park, a long slender cascade of water broken at the top by the streams feeding it. I wonder where all the water comes from. We finally arrive at the Shakti rest house. Kimi Ram, our cook, whose eyes sparkle with laughter and kind energy has whipped up a meal of potato dahl and chapatis (tortilla-like bread) before I can unpack my sleeping bag.

The next day is a 12 km hike to Dhel. I am warned it is a steep ascent (from 2100 meters to 3700 meters, or close to one mile). This is beyond my hiking experience so it is pointless to imagine what to expect. Ashish, our 24-year old crew leader, offers trekking advice: “Breathe through your nose and to determine the appropriate pace, follow your breath.” I become aware that if I go too fast I start loosing my breath and with it my physical and psychological strength. So, I heed his words and follow my breath. I reflect inwardly at how similar this is to my years of martial arts and meditation practice. Ashish continues: “When the going gets difficult PAY ATTENTION to what you are doing. If you want to look around, stop and look, then continue.” I find he’s right and this enhances the experience of both walking and looking and am reminded of the admonition to PAY ATTENTION at Zen sitting sessions. I perceive I’m moving slowly and take short rest stops just sufficient to recharge. I am one of the first to arrive at Shakti and Ashish laughs.

A village dog joined our party the first day. After we set camp, he becomes very alert and points to a knoll at the forest’s edge about 75 yards away. There we see a Red fox, with it’s characteristic white tipped tail tip. The fox is unconcerned by our presence, noses around, and watches us as we watch him. He then nonchalantly, returns to the woods.

Sanjeeva, the park director, suggests we hike up to a ridge above camp for sunset. At the top, a small Hindu shrine awaits us. Three men join us coming up from the valley below. They add some red flags to the shrine, say their prayers of thanks, and offer us some walnuts they have gathered on the way up. I wonder who they are and where they came from. We gaze across the deep valley filled with green trees and dotted with an occasional village, like lichen on the landscape. There are mountains upon mountains in the distance changing to treeless brown at their tops; some peaked with snow. We sit in silence and look. The Sun sets in the west and simultaneously a full Moon, rises in the east. Sanjeeva notes that this is an auspicious moment.

Up at 5:00 AM to greet the dawn and to observe any large mammals. We scatter through the woods in an area where one of the Park rangers has found Himalayan Brown bear scat. The ground is also turned over by their digging. Earlier, this same ranger had identified leopard scat with dog hair in it on the trail. Perhaps, this as close as I want to get. I sit quietly for an hour on a ridge, waiting, watching. The birds awake nosily to greet the Sun’s welcoming warmth. No animal sightings but I feel peaceful, quiet, calm, and very much present in all this beauty.

We enjoy a full days rest ending it up on the ridge for another sunset. Two foresters, Tanadal and Balacram, have come up from Thirtan Valley, where we are headed to be our guides. They look to be my age but I am told they are ten years younger. Tanadal often scans the surroundings with eagle eyes. Balacram, is thin and wiry, and I’m told he knows these mountains like I know my neighborhood. He has smiling eyes with a hint of seriousness that makes you feel you will fall in.

Next morning we are off early for our descent into the Tirthan valley, and we start ascending to 4100m. I am learning not to take what is said too literally. At the top of a ridge we rest, bask in the sun and treat our eyes to the ever-present magnificent vista. I’m feeling good thinking the hard part is over. But then, the descent starts for real. Sanjeeva says we must stick together as it is a dangerous trail. I find myself on a very narrow path perhaps twice as wide as my foot. On my left is a shear rock wall and on my right an abyss into a deep canyon. Balicram is directly behind me carrying a three-foot ice ax. As my right foot slides a little, his ax is immediately implanted between me, and the abyss. My pride is stung as I consider myself athletic, sure-footed, and careful. The feeling passes immediately. I realize he is there to help and we are all responsible for each other moving on a trail above the long fall below.

We stop at a small ledge and huddle together for a rest. Payson breaks out the special milk and sugar chapati, his Indian sister-in-law made for the trip, to give us extra energy. We share them and our porters smile with appreciation and praise. Suddenly Blue Thar (large, mysterious mountain goats) are spotted 100 yards below us feeding on the vegetation. Payson pulls out the video camera and scrambles to the edge, seemingly oblivious to his precarious position. I know how enthusiastic and focused he can get. As I follow him, I feel an internal jolt realizing that there is precious little safety margin. I grab his ankle in a vise-like grip as he strains over the ledge toward the Blue Thar. We get our footage and the sure-footed Tar dash away, covering the distance it took us 45 minutes to pass in five! We crawl slowly and carefully back. My eyes meet Payson’s and we silently acknowledge our exhilaration.

At the bottom of the descent, my expectation that we are almost at our next camp is dashed. I must now muster additional physical and psychological resolve for trekking two more hours. It is near dark when we arrive and my usual ability to generate heat is flagging. Fortunately, the tents have just gone up and I get into my down bag for a sorely needed sleep. Payson wakes me with a bowl of miso (soy) soup that he has brought from the U.S. It is fortified with fresh garlic and I feel the comforting warmth return to my body. This was a difficult and demanding day that pushed me to my limits. I would not have changed a minute of it.

The next evening after another rest day is the important Indian holiday, the Devali. We celebrate with a big campfire and song. A cooking pot becomes a drum. Payson joins in with his flute. The young porters and older guides all sing. They are traditional songs telling of shepherds, love, life in the mountains and the gods who protect them. Smiling eyes sparkle in the firelight and voices rise and fall with the flames. We are all happy, new friends.

During our last day’s descent, Balicram spots a deer about 50 yards away in the dense forest. I am finally able to find it with the aid of the binoculars and much prompting. I can’t believe he found it with his naked eye. As we move down the trails I marvel at the change of the ecology: sparse scrubby vegetation changes to bushes. Alpine meadows transform into denser forest and bamboo groves. My book learning becomes a concrete, experiential reality.

As we wait at the trail end for our jeep, I reflect on this experience. I encountered physical and psychological challenges and found greater self-knowledge in meeting them. There was the vast variety of natural beauty: forests, waterfalls, rushing rivers, vistas of the infinite mountain ranges. My body, mind, and heart have expanded and these experiences, pictures and impressions will be part of me for the rest of my life.

Payson R. Stevens (Del Mar, California)

October 2000, Jiwanal-Parvati Trek:

This trek was one of the peak Nature experiences of my life (along with trekking in Antarctica, the Grand Canyon, and the Nepal Himalaya). GHNP is a gift from the people of India to the people of the world. It is a tangible symbol of their effort to protect a dwindling and unique environment for posterity.One moves through many zones of the forest: from lush lowlands up into the arid and cold higher elevations. Nature is constantly changing and reminding you of how life adapts at so many levels. The trek, at times, is very strenuous. If you’re going to do this one, make sure you work out for two months in advance to get in shape. Your breath and stamina must be strong. Trekking Phanchi Galu is hard work but the rewards and visions will become part of your great life memories. I could continue with superlatives but perhaps this poem, written as we ascended through the Phanchi Galu Pass (4636 meters), will provide another kind of impression.

Phanchi Galu Pass

let the cold pure wind

empty my lungs

of my current life

here under the silhouette

crags and stars.

freeze my past

and leave it behind

as one ice crystal

on the alpine grass.

let the air currents

empty my mind

as I balance each step

for i have dreamt of the

snow leopard

beckoning me onward

to the place i’ve studied

and now visit;

no more symbols,

no more science,

almost no more art.

silence.

let the wind stop

so I can collect my thoughts.

let the wind start

so I can let them go,

last words taken on thermals.

let the mountain devtas*

take my breath

transform my thought

into energy;

here at the high pass

I offer my life

to the wind.

*gods

Copyright 2000, Payson R. Stevens

Blanca Zuluaga (Colombia)

Khorli Poli Trek, GHNP August 2006

Economist

Lecturer at Icesi University – Colombia

PhD. Student Catholic University of Leuven- Belgium.

“As they step into the same rivers, different and still different waters flow.” So said the Greek philosopher, Heraclitus. His timeless observation reminds me how I felt everyday while trekking in the GHNP: walking through the virgin-like paths, listening to the birds, admiring the astonishing shapes of the trees that grow as uncannily as they manage to catch the sun, made me conscious of the permanent movement of nature. Normally, continuously hearing the same sound for a long while can become tiring, but this is absolutely not the case when such constant sound comes from a river. I will keep missing the strong stream of the Tirthan River that was present each second during my trekking days. The experience of waking up with the smell of the mountains, the red and orange sunsets, resting next to the fire after a long walk, is unforgettable. Now, more than ever, I really wished we could be able to preserve this gift of nature as extremely beautiful as it is today.

Kanchi Kohli (India)

Into the great mountains, from “The Hindu”

published in India–June 4, 2006.

The Tirthan valley in Himachal Pradesh is a heady combination of spectacular landscapes, mystic forests and musical birdcalls.

“RIGHT up there and a little further!” That was the response to my question on where our trek was taking us. When I looked up, I asked myself whether I would be able to make it. But then, that’s what I was in the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP) for and it was not an opportunity to be missed.

The GHNP is a 754.4 sq km. protected area located in Kullu District of Himachal Pradesh. Its final notification as a National Park happened in 1999. The park comprises the watersheds of Jiwa, Sainj, and Tirthan rivers. Our trek was to be an exploration of the Tirthan valley.

The walk began at Gushaini village, which is eight km from the park boundary. From there it was two km to Rolla. This, we were told, was like a walk in a garden! The tough part was yet to come with the next hike being a six km climb straight up to an alpine meadow at the height of 3100 m. Of course, this was easy compared to tougher treks, with the highest peak being 5800 m.Our destination was Kholi Poi (the empty trunk of a large tree). The climb was tough but thankfully achievable. I thought I would be aching by the time I reached the top, but, to my surprise, that was not the case. Every breathless step that I had taken seemed history once we reached our destination late in the evening. The cold and crisp mountain air can be such a healer.

What was interesting about this trek was that we were travelling with a set of young villagers who live in the Eco-development zone around the GHNP. They, along with a local NGO, SAHARA, were part of an eco-tourism team that helped guide treks such as ours. Needless to say, they also helped carry the tents that kept us warm and the rations that energised us with every meal. But that was not all; each one of our fellow trekkers knew a lot about these forests, and ran across them with the ease of a mountain goat.

The GHNP is an area extremely rich in biodiversity. It supports a vast variety of flora and fauna. A visit to the website put together by a group called Friends of GHNP (www.greathimalayannationalpark.com) , throws up some interesting facts. When it comes to fauna, the GHNP is home to large mammals like the Himalayan Tahr, Black Bear, Goral, Bharal, to a variety of endangered pheasants like the Western Tragopan, Monal, Koklas and so on. In fact the park is known as the most important area in India for the endangered Western Tragopan. I am not an ardent bird watcher, but being in the company of those who are, allowed me to catch a glimpse of a range of small and big avifauna.

The second day of our trek allowed us to explore the areas around the alpine meadow. We trekked down through a fine bhojpatra forest and got the feel of the trunk on which a lot has been written. It peals out beautifully to give us what was used to write on, much before paper arrived on the scene.

But during the course of our trip, a different set of realities also came up in discussions. Before the area was declared protected under law, local communities accessed these forests for a variety of uses, including grazing, collection of medicinal plants or the rare and precious mushroom (guchhi). The park authorities are working with the communities living in the eco-development zone of the area to look at alternative livelihoods and try to be as sensitive as they can in the given scenario. However, the simple reality is that none of these can completely compensate the people for the rights that they have lost.

Another disturbing reality is that a series of 11 hydel projects are planned in the Tirthan valley alone. Some of these might not be very large, but cumulatively could lead to changing the face of this “little exploited” valley.

But for now, the valley presents spectacular landscapes, mystic forests, musical birdcalls, and melodious streams. Every step is a revitalisation of one’s soul. I was lucky enough to be there to explore this untouched habitat, and be one with nature.

Impressions of Indranil Datta

Indranil Datta, one of the visitors to the Great Himalayan National Park, shares his experience.

“I visited the Great Himalayan National Park for the second time in May of 2022. My first visit to the park was in 2017, right after completing college. Accompanying me was a friend, and both of us were keen on exploring a park that hadn’t yet been overrun by tourists and gypsies. GHNP seemed like the most promising choice. How right we were!

The trek that we undertook back then lasted no more than 3 days. We felt it was too short a sojourn. And couldn’t wait to return for a longer stay, which we eventually did, this year. While the areas around the park seem to have gotten busier, the park itself was as pristine as ever. Over five long days of trekking, we came across only a handful of tourists, and that too only for the first and the last days – the days in between in went in blissful isolation. We camped by ourselves in the midst of a bowl-shaped meadow with the views of the eternal snows right in front of us. The nights – though bitingly cold – were spectacularly lit by a sea of stars, which my eyes couldn’t seem to drink enough of. Despite my passion for nature, I remain an amateur birder and thus, the many feathered wonders that I met along the way remain unidentified. Yet, their presence was a glorious addendum to the trails we walked on – often sparking a flash of envy, as I sorely begrudged their abilities to soar over the hills we had to tiresomely trudge through.

The Great Himalayan National Park remains high up on my list on ‘Most Preffered Wildlife Destinations’. It’s beauty and grandeur have few parallels. And I only hope that it’s spell remains untainted by the shadow of unregulated tourism.”